TRAUMA OF THE PEOPLE

- in the wake of the Beirut Explosion

IT WAS EARLY in the evening on August 4th 2020, when the third largest explosion in history went off in the port of Beirut, sending seismic waves through a country already forced to its knees. The country was in the midst of an abysmal economic crisis, and an unemployment rate of more than 35 percent. Tensions between sectarian groups had led to violent protests across the country over the past year. A pandemic had already filled the hospitals and corruption was permeating every stratum of society.

The pressure wave from the explosion spread at 300 meters per second, tore walls apart, blew doors in and smashed all the glass. Afterwards came the opposing pressure wave, which retreated towards the epicenter of the explosion. Tremors from the explosion could be felt across Lebanon and even in Cyprus, which is more than 200 kilometers out in the Mediterranean.

The explosion force was equivalent to an earthquake with a magnitude of 3.3 on the Richter scale.

The crater after the explosion is so large that it can be seen from space.

About 220 people lost their lifes, more than 6,000 got injured. The violent explosion has left at least 300,000 homeless and the reconstruction is estimated to cost more than 5 billion USD.

Following the explosion, the Lebanese government resigned and the civil society literally cleaned up after the corrupt regime, that had neglected 2,750 tonnes of ammonium nitrate stored in the middle of the Arab world's most progressive capital.

Now the future has been placed in the hands of the historically sturdy, and deeply traumatised people.

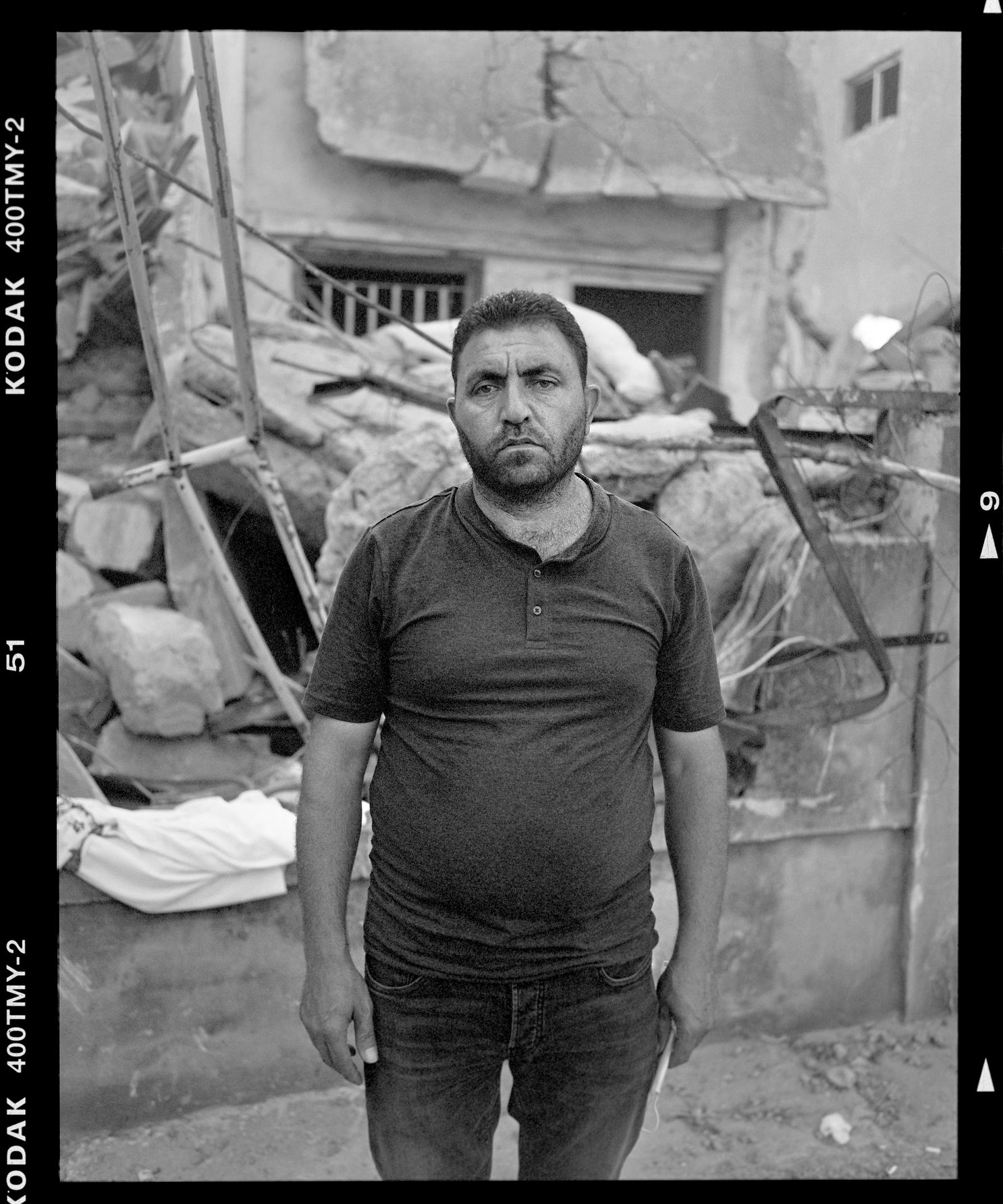

Ahmed Haj Mustafa from Syria lived with his family in the Mar Mikhael area just opposite the port. When the explosion hit, he hurried out onto the street where he found three of his daughters. While he himself stayed with two of the children, while his 22-year-old daughter went into the house to save his wife and their 3-year-old daughter.

Shortly after, the house collapsed, killing all three.

The port of Beirut was Lebanon's lifeline. Over 80 percent of the country's trade is imported through here, and the iconic silos were the country's most important grain storage. The explosion pulverized 90 out of a total of 104 silos.

The Shia militia Hezbollah has a certain amount of control over the port, because of their role in the Lebanese security service and military.

It is unknown whether the ammonium nitrate, which has now been blown up, was to be used for weapons.

When 27-year-old Bruna Dagher woke up in the dust of shattered glass, with fractured bones in her face after a door flew into her, she was not afraid.

“I was not sad or scared. I was filled with anger. "

She has been active in the fight against the regime, which she calls an Italian mafia on a national scale, for a long time. The explosion has become the occasion for a final showdown with the power elite in Lebanon.

“We are well educated from the middle class, but completely without opportunities. Lebanon is a failed state. We want to travel, but at the same time we know that the corrupt politicians are staying in the country. And we will not leave the country to their sheep. ”

Cynthia came to Beirut through an agency that promised her work with good pay and the opportunity to save up to go to college back home. When she arrived at the airport in 2014 as a 20-year-old, she was told her documents were fake and was forced to sign an employment contract.

For two years she worked as a maid under slave-like conditions.

She slept on the floor, ate the children's leftovers, was abused and was not allowed to leave the house. One day she ran away from the family, and lived off the grid with the other Kenyan women in similar situations.

After the explosion, many of the women have been left on the streets, and now they have gathered in a camp in front of the Kenyan embassy.

"I just want to go home to my two children in Nairobi, and find a way to create a better future for them."

The 2,750 tonnes of ammonium nitrate had been confiscated and stored at the port without security measures for six years.

Ammonium nitrate is typically used for fertilizer, which is why it is typically stored in large quantities in warehouses.

If ammonium nitrate catches fire, it can burn to the point where it suddenly explodes. In a fraction of a second, all the solid is converted to gas, creating a pressure wave.

Investigators are looking into whether it was a stock of fireworks in the port that caused the building with ammonium nitrate to explode.

Nicolas Sadar was sitting on the couch when the explosion happened. Doors and windows flew through the room, but luckily he survived as he sat protected by the wall.

He is 80 years old and has lived through all of Lebanon's hardships, including a 15-year civil war, and several Israeli attacks in Beirut.

"How much more can people take? As long as politicians are corrupt, there is only one future in sight. Total destruction."

He gets no money from the government. Usually, he lives off the interest from his savings, but the bank have frozen them. Now an NGO is fixing his apartment.

Syrian girl on the street in the torn Karantina neighborhood.

It is estimated that since the civil war in Syria began in 2011, about 1.5 million Syrian refugees have arrived in Lebanon.

Lebanon's constitution states that the president must be a Christian, the prime minister must be a Sunni Muslim, while the parliamentary leader must be a Shia Muslim. This distribution of power was made to avoid tensions, but the country's kleptocratic leadership with a politically-sectarian fragmented elite is often blamed for running the country to the ground.

Mustafa, 12, from Syria.

By 2020, Lebanon was already plagued with a government debt that is described as the world's largest. The corona crisis pushed the country beyond an economic abyss and the Lebanese pound has lost 80 percent of its value since March.

It is estimated that 60 percent of the population will live below the poverty line by the end of the year.

Lieutenant Georg Alkashi has served in Beirut's fire brigade for 24 years. When he received the first emergency call on August 4th, he dispatched, as always, 9 firefighters and an ambulance with 1 paramedic. Shortly afterwards, the call came for backup.

The backup firefighters had just reached the station's courtyard when the explosion tore down walls and windows over the area where the crew had just rested.

“No matter how much we have suffered, we have done it for nothing. We went into the fire for them. We did not know what was in there, but they did. Now we have lost 10 men, all our ambulances and all our fire trucks. But that's our job. Our life. We will always continue to help the people. ”

Most residents of the Karantina area live in poverty and cannot afford to rebuild their homes. In the weeks following the explosion, it became clear that the Lebanese state would not take responsibility, and the initiative was solely with civilians and NGOs.

Volunteers from the NGO Offreja are helping to rebuild Karantina. Many have come from France to help as they feel a historical kinship with the Lebanese people.

President Macron was also one of the first to visit Beirut after the disaster.

"Lebanon is no longer able to finance itself," Macron said.

Dr Joe Baroud is a plastic surgeon, and was in his clinic 5km away when the explosion hit. He was called in to provide emergency assistance, and saw many severe glass injuries to people's faces and bodies. Since then, he has offered free surgeries and cosmetic improvement of the scares, so people do not have to carry the trauma with them for the rest of their lives.

"Appearance is important, not to make the burden even worse. I want to give people some hope. A little joy."

The strength of the civil society makes Joe Baroud proud to be Lebanese. Everyone volunteers with him around the clock, but he does not believe the change in Lebanon will happen fast.

"After 30 years of corruption, it will probably take 30 years to get out of it. As it looks now, the government is demanding that I pay taxes even on donated materials for the operations. In dollars."

The port has always been a symbol of the trade and freedom, that has given Beirut its reputation as the Paris of the Middle East.

Some of the areas that were hardest hit, were at the same time some of the city's most progressive and well-visited.

However, due to summer vacations and corona lock downs, there were fewer people on the streets than normal.

Beirut's physical condition after the explosion is unimaginable.

Ritaj Zaknoun is 18 and a journalism student. She hands out toys to Karantina's children after the disaster.

Since October, she has been to all demonstrations against the government. She sees no other options.

"I'm a human being, that's what I'm obliged to do. I must have my rights. I cannot be silent."

Sarah Asmar is 23 years old, an art student and model. She thought it was an earthquake that hit.

"I have not been down in the ruins. This is where we went out. It was the symbol of the fun, open, amazing Lebanon. Now it is ruined. I have never wanted to leave my country. Until now. I have no motivation anymore.”

She protested against the government in the fall, but stopped because of Corona, and because she felt it did not have any effect.

She hopes that the explosion can, after all, provide Lebanon with outside help.

“My generation is tolerant and does not go up in the old religious conflicts at all. I just want peace. ”

All investigations indicate that the explosion was due to an accident, but in a country that since 1975 has been marked by either civil war, foreign invasion or neighboring countries' intelligence services, there are a lot of conspiracy theories going around.